After a warmer than usual December, many ski resorts across the nation are finally able to open.

The beginning of January threatened to be the start of a disappointing ski season. Many resorts had reported little to no snow. The situation rapidly changed when the country was gripped with record snowfall and record low temperatures, yielding enough snow to allow resorts to open. The website, onthesnow.com, lists resorts that are open and projected dates for others across the nation.

The anticipation and exhilaration of skiing or snowboarding in fresh powder is unmet in any other winter sport. However, heading to a mountain at a higher altitude than you are used to can result in altitude illness.

Altitude Illness

According to the The CDC Yellow Book (health information for international travelers):

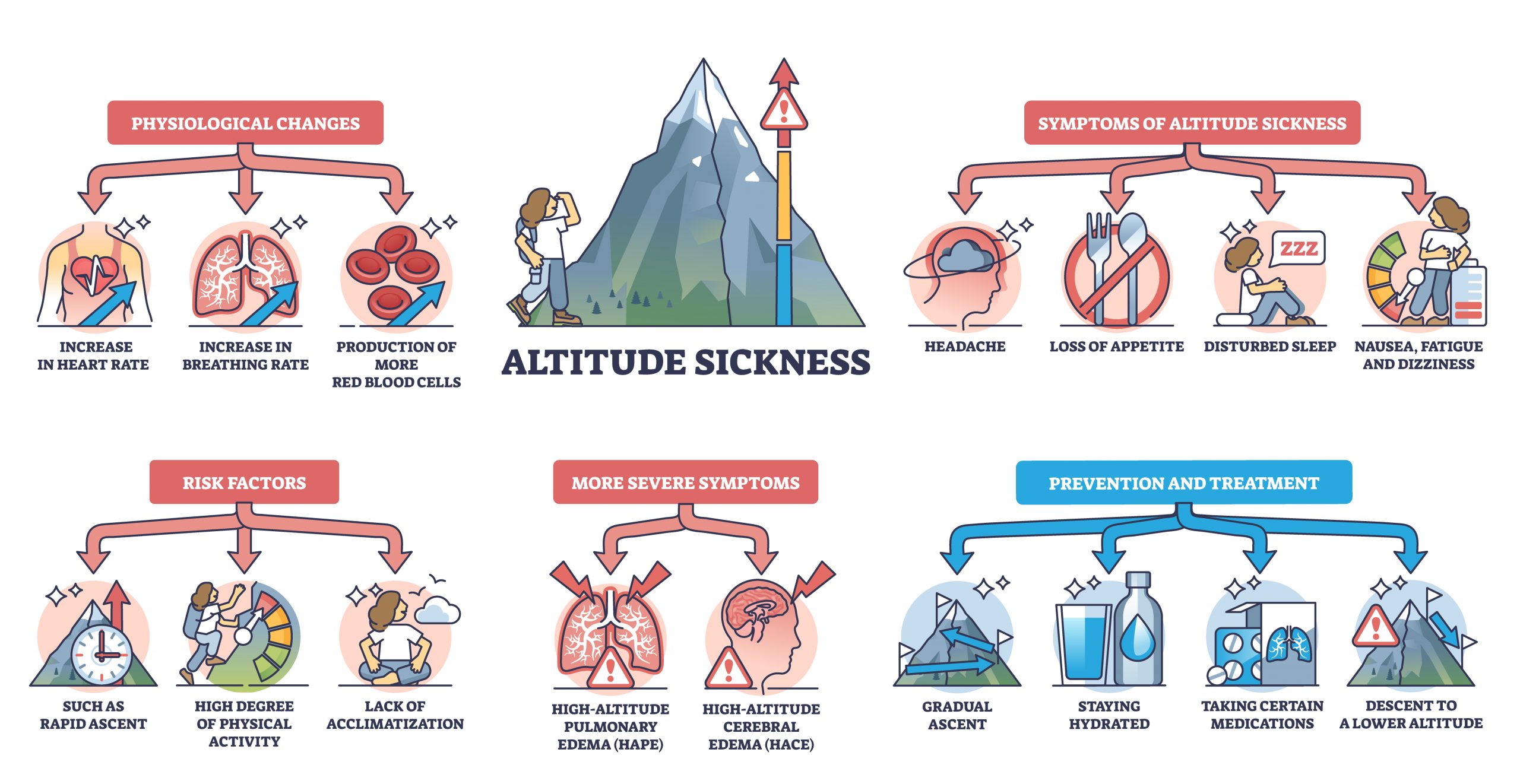

Altitude illness occurs at altitudes of 8,000–10,000 ft (≈2,440–3,050 m). (Sometimes lower altitudes, as low as 6,000 fee or 1829 meters), that can cause hypoxic stress.

Hypoxic stress results from decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the air at high altitudes. The decreased partial pressure of oxygen results in lower arterial levels of oxygen. The tissues that the arteries serve become oxygen starved, leading to serious health complications.

There are three types of altitude illness syndromes

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

This is the most common form of altitude illness. It affects 22–53% of travelers in altitudes between 6070 feet and about 14,000 ft ( between 1,850 and 4,240 meters), with higher incidences being described at the higher elevations. Onset of symptoms usually occurs rather quickly- within 2-12 hours after arriving at a high elevation or ascending to a higher elevation.

Symptoms of AMS include:

- headache,

- nausea,

- vomiting,

- fatigue,

- dizziness,

- and insomnia.

Very young children with AMS can develop loss of appetite, irritability, and pallor.

AMS can resolve within 12–48 hours if you do not continue to ascend.

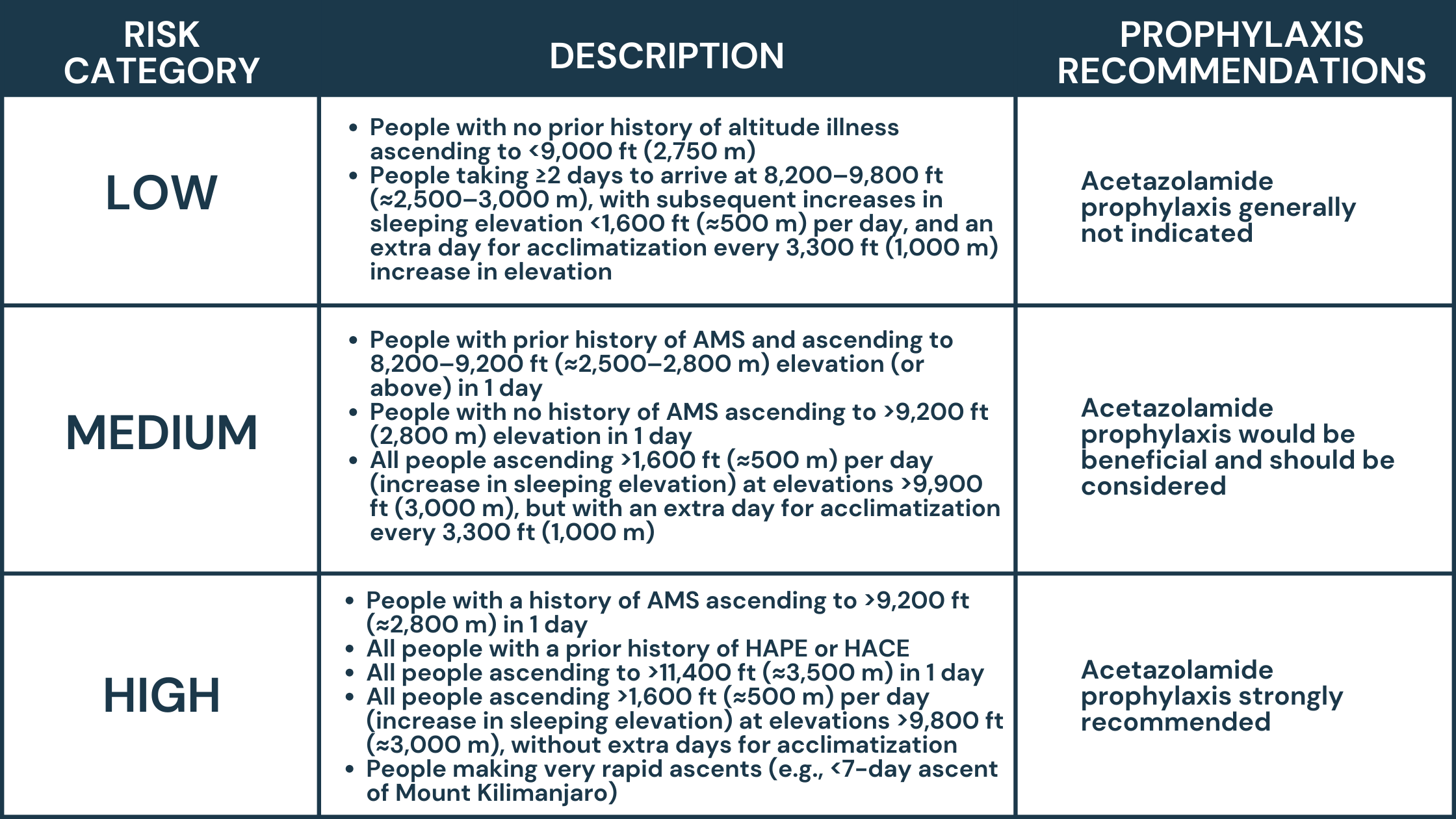

Acetazolamide, taken before ascent can help prevent altitude illness in those predisposed, (history of altitude illness, rapid ascent to destination) and can shorten duration of altitude illness from 3-5 days to 1 day. (Acetazolamide is one of the Jase Case add-ons.)

If not appropriately treated, AMS can lead to HACE and/or HAPE:

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

(HACE is rare form of high-altitude illness, causing cerebral edema and is fatal if not treated) Although HACE presents with similar symptoms as AMS, cerebral edema can lead to:

- Altered mental status

- Confusion

- Drowsiness similar to alcohol

- Coma and death if not promptly diagnosed and treated (within 24 hours)

In populated areas with access to medical care, HACE can be treated with supplemental oxygen and dexamethasone. In remote areas, initiate descent for anyone suspected of having HACE, in conjunction with dexamethasone and oxygen, if available. If descent is not feasible, supplemental oxygen or a portable hyperbaric device, in addition to dexamethasone, can be lifesaving. Coma is likely to ensue within 12–24 hours of the onset of ataxia in the absence of treatment or descent.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

HAPE is characterized by progression of symptoms over 1-2 days

- Reduced exercise tolerance

- Exertional dyspnea, and cough, followed by dyspnea at rest

- Cyanosis

- Productive cough with pink frothy sputum

- Oxygen saturation values of 50%–70% are common.

Can rapidly progress to

- Bronchospasm

- Myocardial infarction

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

Immediate descent from high altitude is almost always necessary. If immediate descent is not an option, use of supplemental oxygen or a portable hyperbaric chamber is critical.

Patients with mild HAPE who have access to oxygen (e.g., at a hospital or high-elevation medical clinic) might not need to descend to a lower elevation and can be treated with oxygen over 2–4 days at the current elevation. In field settings, where resources are limited and there is a lower margin for error, nifedipine can be used as an adjunct to descent, oxygen, or portable hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Descent and oxygen are much more effective treatments than medication.

Risk factors for altitude sickness include:

- Traveling to the area too fast, not allowing the body to acclimate (allow 3-5 days gradual ascending to destination). This puts you at a lower risk for altitude illness than those who arrive at the higher altitude without allowing the body to acclimate.

- Genetics may play a role; this is still unclear how or if it does.

- Age, sex, physical fitness or training does not preclude one from altitude illness.

Be prepared- don’t let high altitude illness ruin your trip

Start slow- Slow ascent- over a period of 3-5 days can help the body acclimate to the altitude. The Wilderness Medical Society recommends avoiding ascent to a sleeping elevation of ≥9,000 ft (≈2,750 m) in a single day; ascending at a rate of no greater than 1,650 ft (≈500 m) per night in sleeping elevation once above 9,800 ft (≈3,000 m); and allowing an extra night to acclimatize for every 3,300 ft (≈1,000 m) of sleeping elevation gain.

Prevention through medication- With rates of altitude illness reach as high as 53 percent of travelers, medication such as acetazolamide can prevent or curb altitude sickness and should be in every high-altitude travelers medical preps.

According to the CDC, side effects to acetazolamide are rare, however, seek medical attention if you have signs of an allergic reaction: hives; difficult breathing; swelling of your face, lips, tongue, or throat.

With the add-on acetazolamide to your Jase Case, you can prevent or lessen the time away from the slopes. Be sure to have this valuable medication with you when you travel to high altitudes.

Acetazolamide can also treat glaucoma (acute angle-closure).

- Brooke Lounsbury, RN

Medical Content Writer

Lifesaving Medications

Recent Posts

Keeping you informed and safe.

Medical Readiness: What Really Kills First

When Disaster Strikes, It’s Not Hunger or Thirst That Takes the First Lives In every disaster zone, from hurricanes in the Caribbean to war zones in Ukraine, the pattern is the same. People worry about food and water, but it’s infection that kills first. A small wound...

Exploring Dr. William Makis’ Hybrid Orthomolecular Cancer Protocol: Focus on Ivermectin and Mebendazole/Fenbendazole

Exploring Dr. William Makis’ Hybrid Orthomolecular Cancer Protocol: Focus on Ivermectin and Mebendazole/Fenbendazole *Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes and does not constitute medical advice. Always seek professional guidance.* In the evolving...

Be Prepared for Life’s Unexpected Moments

3 Reasons EVERYONE should have emergency medications avaiable. It's all about access—access to medications and care when you need it most. And when things happen outside of your control that access can disappear.Below are 3 examples of how easily this access can be...

Youth Preparedness: Teaching, Building, and Coping with Disasters

Educating and preparing your children ahead of time means fewer surprises in the event of an emergency.Growing Up Prepared: Empowering Youth in Disaster Preparedness As we observe National Preparedness Month, it's crucial to remember that disasters can strike at any...